How does a plane work? |

||||

|

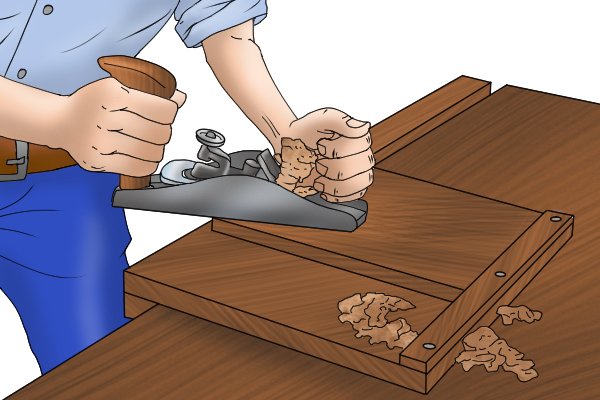

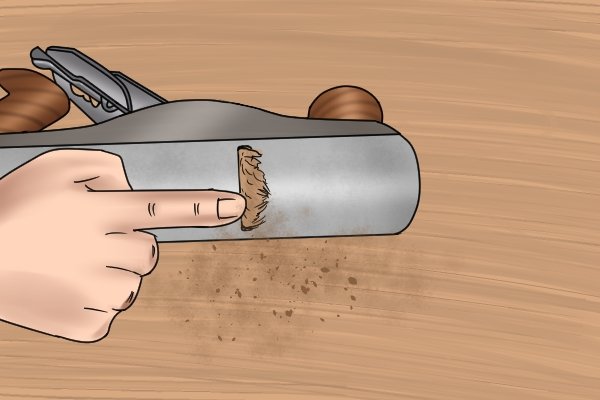

A hand plane works by shaving off thin layers (shavings, or chips) as it is pushed along or across a piece of wood. This reduces the wood to the required size, levels it, puts a smooth finish on the surface, or cuts a recess that can be used in joint-making (joining pieces of wood together). | |||

Avoid doing the splits |

||||

|

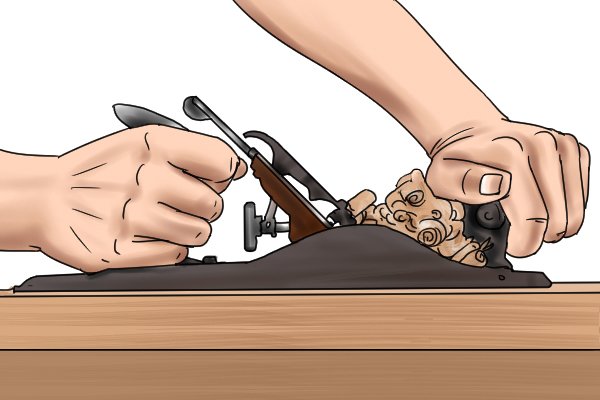

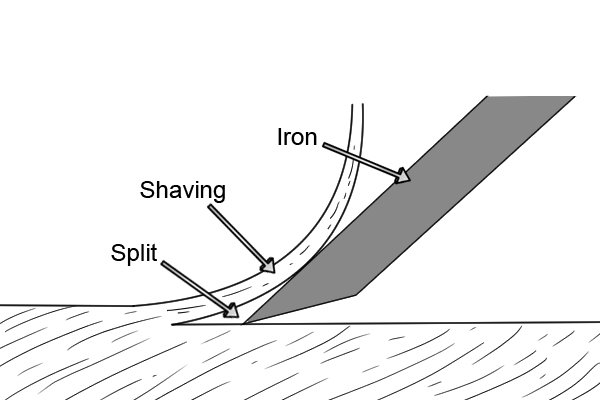

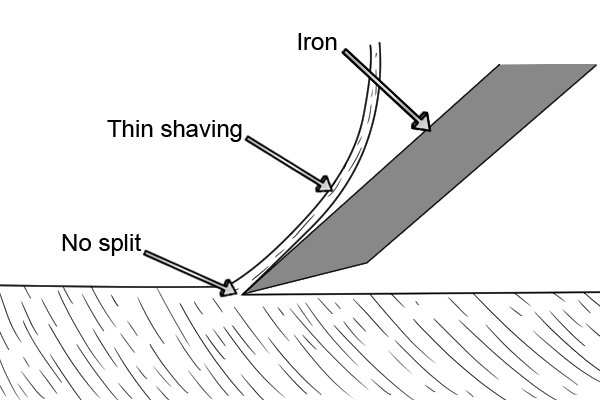

As the iron of a woodworking hand plane cuts a piece of wood, the chip must be bent and levered out of the way as it slides up through the throat of the plane, otherwise the chip might act as a kind of lever that splits or tears the wood. | |||

|

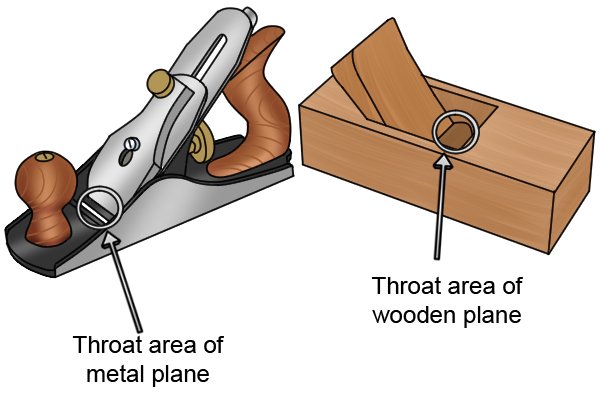

The throat is the area above the mouth and in front of the lever cap or, in the case of most wooden planes, the wedge. | |||

|

If the cut is deep, the force needed to bend the shaving may be greater than that required to separate wood fibres. If this is the case, the result is a split in front of the blade. | |||

|

However, if the shaving is thin, it will bend away to allow the blade to move forwards with very little or no splitting. The result is a smoother cut. | |||

|

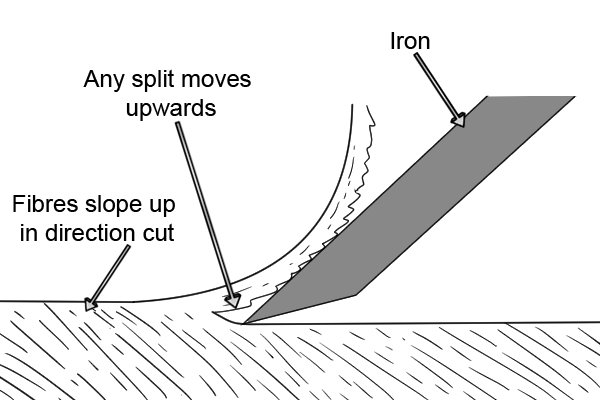

If the grain of the wood is not exactly parallel to the surface, the workpiece should be positioned with the fibres sloping up in the direction of the plane motion.This ensures that any split that develops moves up into the wood that will be removed as a shaving. | |||

|

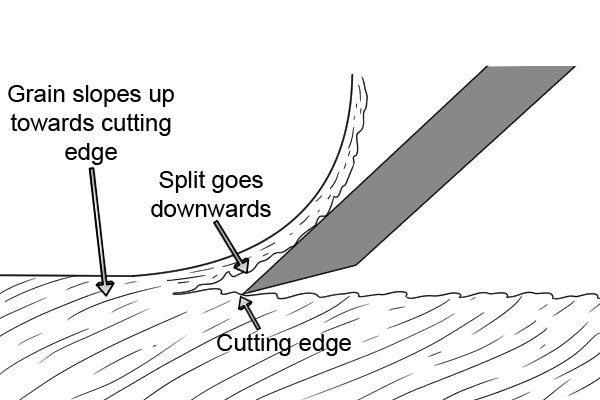

Cutting with the grain sloping up towards the cutting edge of the iron, on the other hand, would cause the split to enter the surface you are trying to make. The shaving is stronger and more likely to widen the split. | |||

|

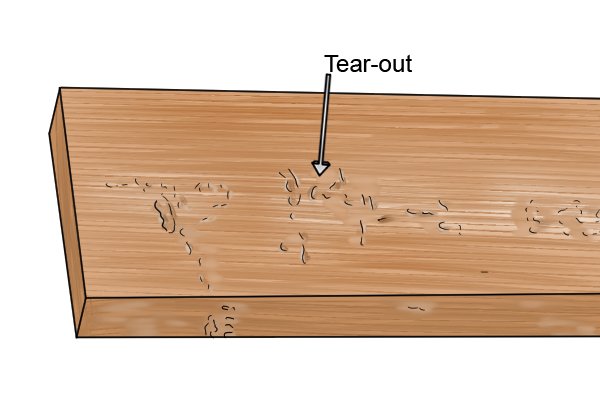

||||

|

Either a rough surface is created through what’s known as tear-out (wood being torn out rather than cleanly cut) or the plane comes to a sudden, jarring halt. Bear in mind that wood grain can change direction quite often along the length of the workpiece. | |||

|

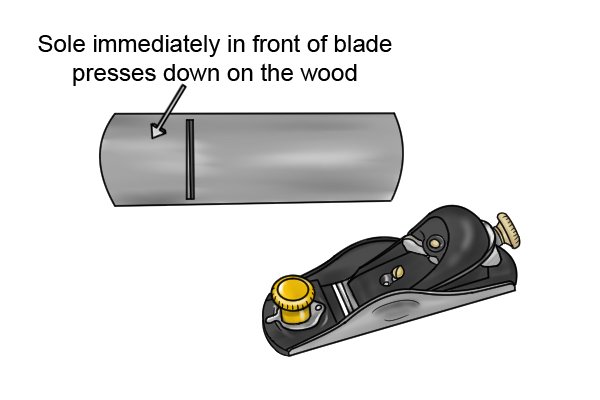

The plane’s body helps to avoid problems with this in two ways. As well as preventing the blade from digging in, the sole of the plane immediately in front of the blade presses down on the wood and tends to restrain splitting. | |||

|

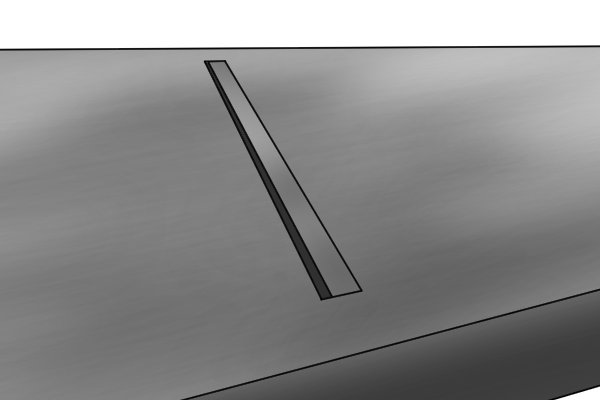

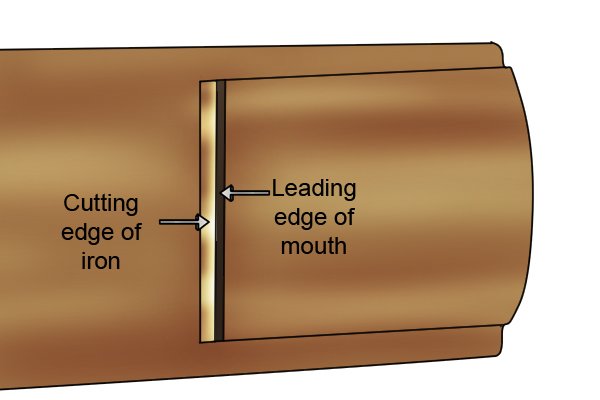

The closer the cutting edge of the iron is to this section of the sole (that is, the narrower the mouth of the plane), the more effective it is at avoiding a split, but the thinner the shaving must be if it is not to ‘choke’ the plane. | |||

|

||||

|

Choking means shavings becoming stuck in the mouth, often very firmly. | |||

|

There is a means of adjusting the mouth opening, or the position of the blade relevant to the leading edge of the mouth, on most metal planes and some wooden planes, to give the most efficient setting for the particular job.A wide mouth is needed when planing wood to size quickly, but a narrow mouth is best for smoothing wood, when the width of shaving is very fine. | |||

|

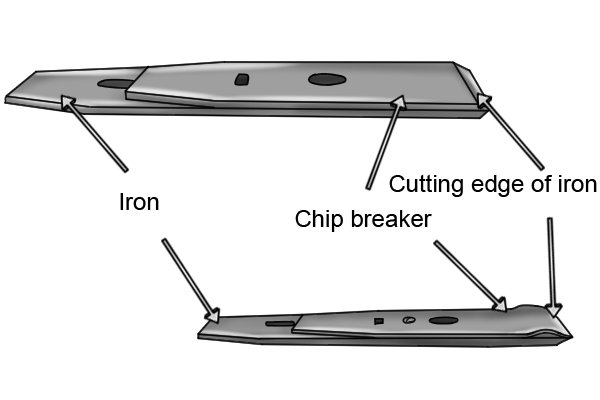

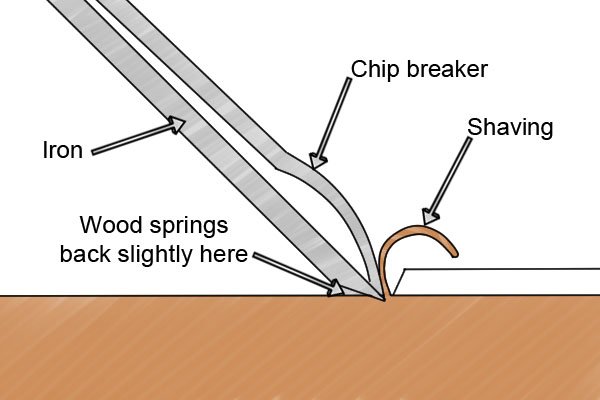

Chip breakerA claimed improvement in the performance of planes was introduced early in the 18th century with the discovery of the chip breaker. |

|||

| A shaving riding up the surface of a single iron (a blade with no chip breaker) gains some leverage, which can help it to initiate a split in front of the cutting edge.The chip breaker breaks or folds the shaving before it has gained too much leverage. With this help, a sharp, well-tuned and finely-set plane can cope with difficult grain. | ||||

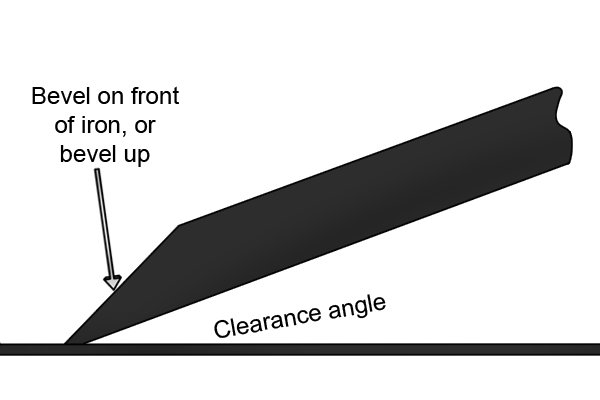

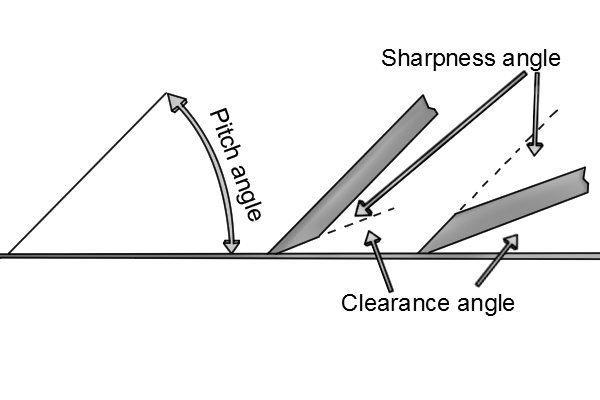

The clearance angle |

||||

|

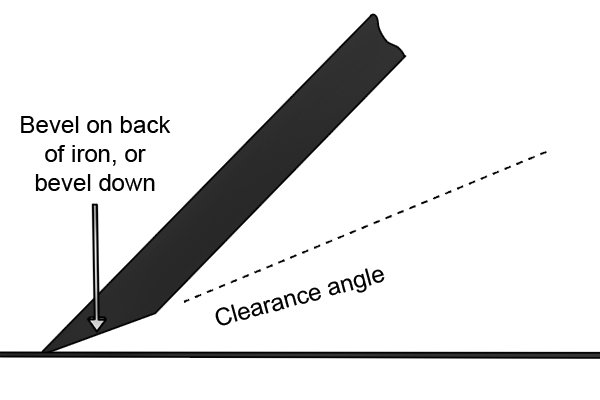

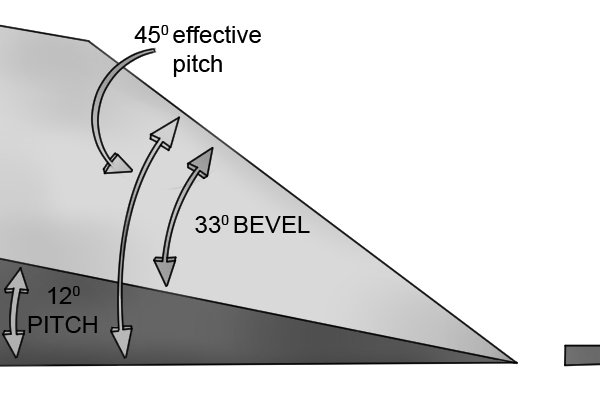

With a bevel down iron, the angle between the bevel on the back of the iron and the wood surface is called the clearance angle.

This is the angle by which the iron clears the freshly cut surface. |

|||

|

With a bevel up iron, the clearance angle is the angle between the back of the blade and the wood surface. | |||

|

The thrust as the plane moves forward slightly distorts the wood, until it yields to the cutting action. Part of this distortion is a downward compression.

As the blade moves on, the freshly cut wood springs back and might lift the plane blade if there is an insufficient clearance angle. |

|||

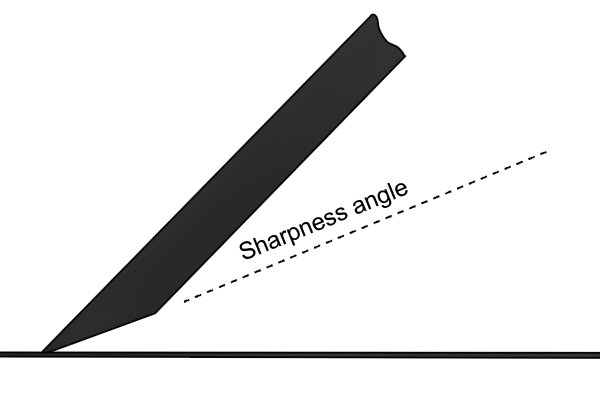

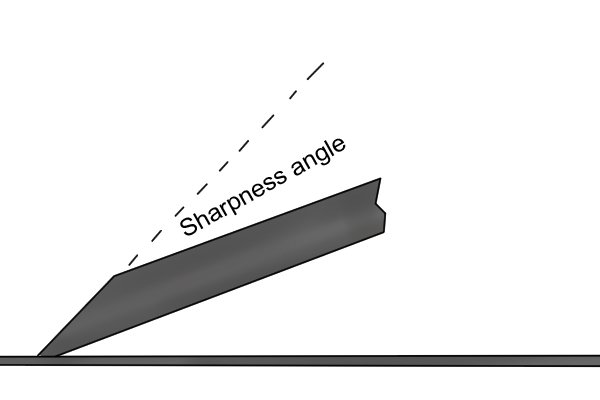

The sharpness angle |

||||

|

The sharpness angle of a bevel-down blade is the angle between the front of the blade and the bevel on its back. | |||

|

The sharpness angle of a bevel-up blade is the angle between the bevel on the front of the iron and the back of the iron. | |||

The pitch |

||||

|

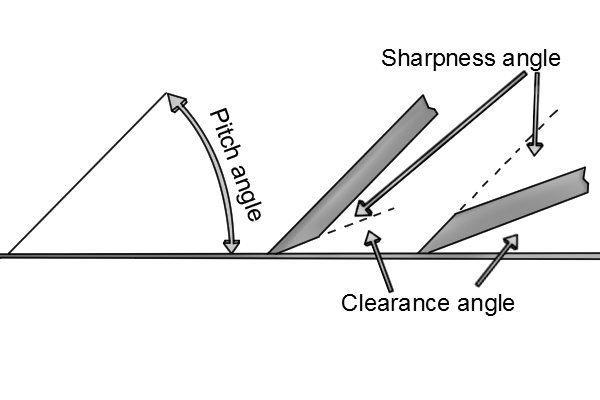

The pitch is the sum of the sharpness angle and clearance angle.

When, for instance, a bevel-down bench plane is described as having its iron “bedded” at 45 degrees, this is a reference to the pitch. |

|||

|

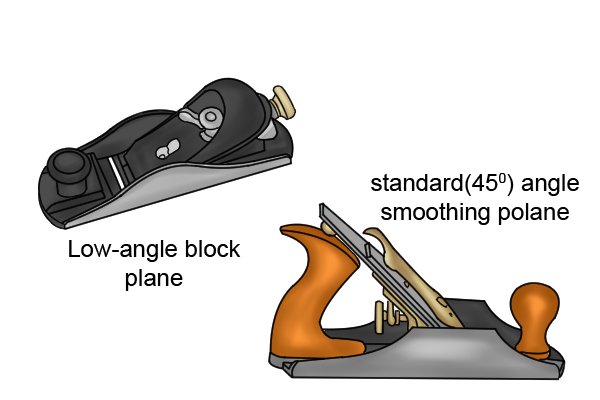

Although some bevel-up planes might be described, for instance, as having their irons pitched at 12 degrees, the bevel on the front of the iron effectively increases the pitch, so in some cases, bevel-up and bevel-down irons effectively have a similar pitch. | |||

|

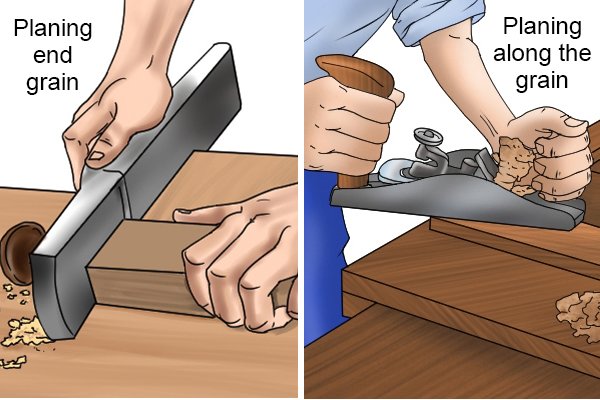

Clearance and sharpness angles and pitches are related to the type of work you want to do with a plane. For instance, it’s best to use a plane with a more acute (lower) pitch for planing end grain, while using a smoothing plane for a perfect finish requires an iron with a greater pitch. | |||

|

When planing along the grain, a lower pitch is more likely to cause splitting than a higher one. When planing end grain, a higher pitch makes cutting the wood fibres laterally more difficult, whereas the slicing action of a lower pitch makes it easier. | |||

|

See What is the perfect pitch for plane irons? for more information about pitches and which one is appropriate for which job. | |||